Why the Struggle for Palestine Is a Struggle Against ‘Fossil Capitalism’

By Adam Hanieh, Robert Knox, and Rafeef Ziadah

Adam Hanieh is Professor of Political Economy and Global Development at the University of Exeter and the author of Crude Capitalism: Oil, Corporate Power, and the Making of the World Market.

Robert Knox is Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Liverpool.

Rafeef Ziadah is a Palestinian organizer and Senior Lecturer in Politics at King’s College London. She is the co-editor, with Brenna Bhandar, of Revolutionary Feminisms: Conversations on Collective Action and Radical Thought.

The past two decades have witnessed profound political change across the Middle East. Even before the genocide in Gaza began, the region was the most conflict-affected in the world, marked by the biggest displacement of people within and across borders. The scale of human displacement in the region exists alongside its extreme wealth disparities: by 2020, some studies put the Middle East as the most unequal of any area in the world, with 31 billionaires holding the same amount of wealth as the bottom half of the entire adult population. Such massive inequalities, combined with a long history of authoritarian rule and recurrent capitalist crises, have fueled two cycles of region-wide uprisings, in 2011 and 2018. A decade of political upheaval has followed these revolts, defined by ever-more violent state repression, armed conflict, and further waves of mass displacement.

These crises have reshaped the region’s internal political landscape and also reflect a deep-seated fracturing of American hegemony in the region. Beginning in the wake of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, many of the established pillars of U.S. influence have eroded, and a bevy of other political forces have emerged that jostle to project their own influence. Regionally, states such as Iran, Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have significantly expanded their footprint, in part through the sponsorship of various armed groups and other political movements. External powers like Russia and China also play a more prominent role in the region’s politics. While there is no other “Great Power” immediately capable of displacing American influence—especially its unrivaled military strength—Washington now faces a region where its dominance is increasingly contested.

This erosion of American dominance in the Middle East is not just a regional phenomenon, but closely tied to a reconfiguration of global capitalism, and with it, global power relations. Of course, most important here has been the emergence of China and the wider East Asia region as rival zones of capital accumulation, industrial production, and financial strength. The Middle East has been pivotal to this eastward shift of the world market: the region’s energy supplies are the lifeblood of China’s economy, and today the great majority of the Middle East’s oil and gas exports flow eastwards, rather than towards Western countries. Beyond energy, a range of other economic interdependencies now link the Middle East, China and East Asia, spanning finance, “green” technologies, AI, construction, and infrastructure investment.

Against this backdrop, American policy in the Middle East has doubled down on the strategic orientation of integrating Israel more fully into the broader regional order by deepening its political and economic ties with Arab states, especially Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf monarchies. This renewed impetus for normalization is not about diplomacy alone—it is about consolidating the region’s primary centers of wealth and power within a single bloc aligned with U.S. interests. It is through this process of normalization that the U.S. seeks to reassert American primacy in the region.

The Push to Normalization

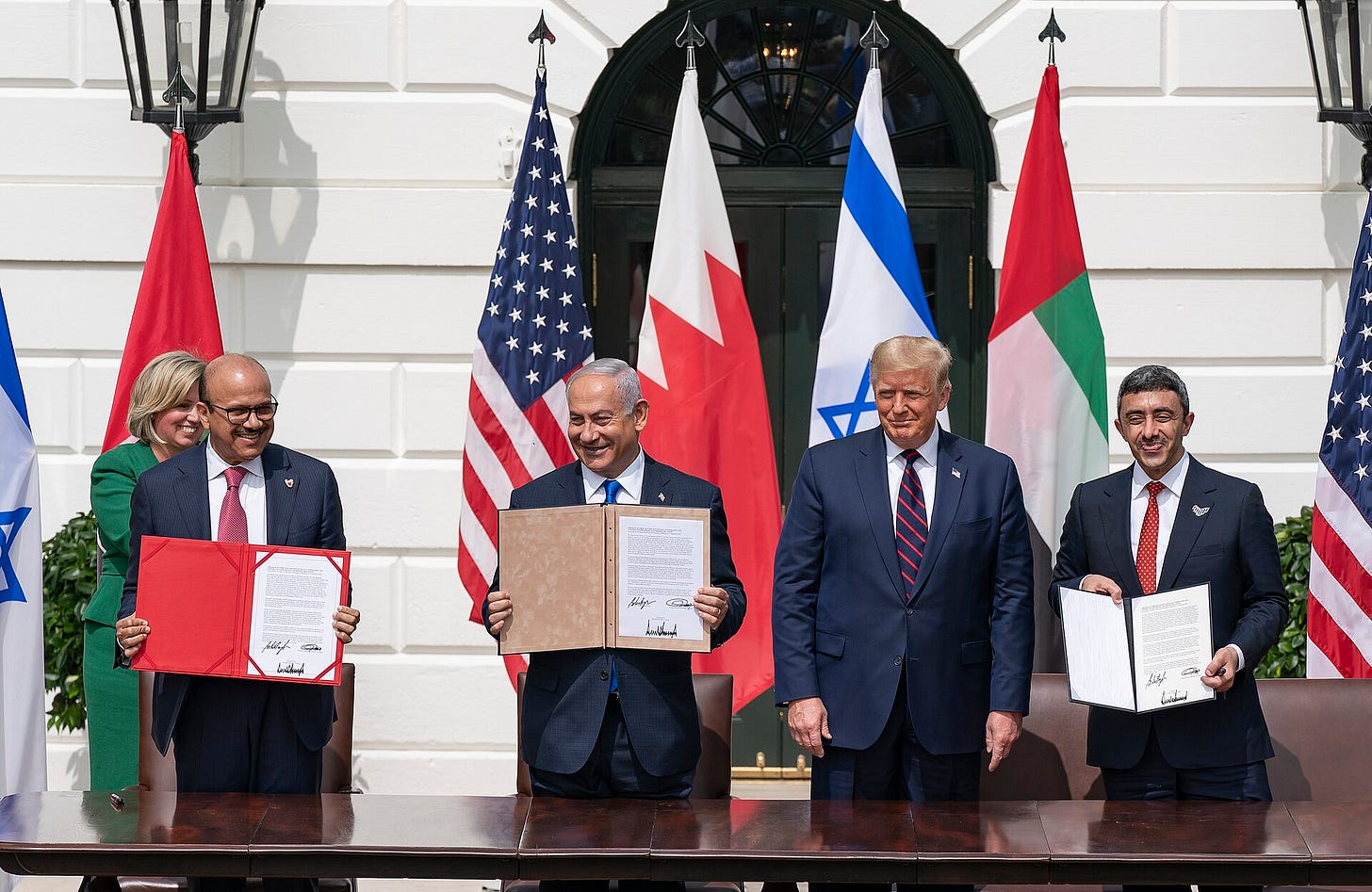

A clear indication of this strategic orientation came with the Donald Trump-backed 2020 Abraham Accords, which saw the UAE and Bahrain formally normalize relations with Israel. This agreement, driven by significant American incentives, paved the way for a UAE-Israel free trade agreement in 2022—the first of its kind between Israel and an Arab state. Trade between the two nations soared from just $150 million in 2020 to over $2.5 billion in 2022. Sudan and Morocco soon followed, giving Israel formal diplomatic relationships with four Arab states. Today, Israel has formal relations with countries representing around 40 percent of the Arab region’s population, including some of its biggest political and economic powers.

With the inclusion of the UAE, the Abraham Accords broke the longstanding taboo on formal relationships between Israel and the Gulf states. But the UAE’s importance to this process is much more than symbolic. As the leading financial center in the Middle East, the UAE is the headquarters of many of the region’s largest banks, and its economic zones sit at the core of inter-regional investment flows that will now include Israeli finance capital. The UAE is also a leading global logistics and infrastructure hub: Dubai International Airport is one of the busiest in the world, and the country runs a leading global port operator, DP World.

The UAE’s financial and logistical capacities make the country a key enabler of the normalization push. This was confirmed in September 2023 with the announcement of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), an European Union-sponsored initiative that was also backed by the United States. IMEC envisions a trade and transportation network linking India to Europe through the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Greece. Though still in its early stages, the project has advanced despite Israel’s onslaught on Gaza. Indeed, during the height of Israel’s bombardment, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi traveled to Abu Dhabi to sign an agreement with President Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan of the UAE, laying out the basic framework of IMEC. For Brussels and Washington, this represents much more than an infrastructure project: by embedding Israel within regional trade networks, IMEC is explicitly framed as a direct challenge to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The impetus for normalization with Israel is not about diplomacy alone—it is about consolidating the region’s primary centers of wealth and power within a single bloc aligned with U.S. interests.

Israeli political and economic leaders fully share these goals of normalization via regional economic integration. This became evident in May 2024, when, even as Israel bombed Gaza, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu unveiled his “Gaza 2035” plan, which proposed transforming Gaza into a regional economic hub, integrating it into the Israeli and Egyptian economies through the “Gaza-Arish-Sderot Free Trade Zone.” The vision included railways, pipelines, and trade routes linking Gaza to global markets. It even presented the enclave as a future center for electric vehicle manufacturing, where cheap Palestinian labor would produce for global supply chains (including IMEC). Within this vision, Netanyahu presented Gaza as a “blank slate”—a territory to be “rebuilt from scratch,” as if Palestinian life, history, and resistance could simply be erased and replaced with a free trade hub. According to Netanyahu, this model might be replicated in other conflict-riven states, such as Yemen, Syria, and Lebanon.

Much like the 1990s claims around Gaza becoming a “Singapore on the Sea,” the Gaza 2035 plan is a nonsensical fiction that largely serves to hide the scorched-earth destruction of Israel’s war machine. But what is important here is not so much whether these plans match reality, but how they work ideologically—projecting a vision of the future in which Israel is integrated into the regional economy, and Palestinians in Gaza become a pool of cheap labor jointly exploited by both Israeli and Arab investors. All of this confirms the ways in which war and conflict can serve as handmaidens of capitalist expansion.

Yet, one outstanding question remains: when will Saudi Arabia agree to normalize its relations with Israel? While Riyadh undoubtedly gave its tacit approval for the UAE and Bahrain to move forward with the Abraham Accords, it has so far refrained from formal recognition of Israel—and this despite a plethora of meetings and informal connections between the two states prior to the war in Gaza. The war put these discussions on hold (at least publicly). But in the wake of Donald Trump’s election, the push to normalization has returned front-and-center to the politics of the current moment.

Paths to Erasure and the Fictions of ‘Sovereignty’

Of course, the prime obstacle to this U.S.-led project of normalization is the ongoing resistance of the Palestinian people, who remain overwhelmingly opposed to such initiatives. These objections are not new—they date back to the early history of Palestinian politics, when the idea of tatbeeʿ (تطبیع), meaning normalization in Arabic, was firmly rejected, and slogans like la lil-tatbeeʿ (لا للتطبیع) (“no to normalization”) became a common refrain across the region, reflecting a broader principle of the movement. Because of this rejection, there is an indelible link between the imperial-sponsored politics of normalization and the attempt to liquidate the Palestinian struggle.

At the heart of this attempted erasure is the question of Palestinian refugees and their right to return to their homes and lands from which they were expelled nearly eight decades ago. The idea of return is much more than an appeal to memory or nostalgia—it is a political demand, which directly confronts the very underpinnings of settler colonialism as a process of permanent uprooting and dispossession.

This is precisely why normalization depends upon severing the fight for return from Palestinian politics, reducing refugees to a humanitarian issue that can be solved as part of “final status negotiations.”

We can see this at work on multiple levels. One is the renewed push to defund and shut down the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), an organization which has provided education, health care, and social services to Palestinian refugees since 1949. Eliminating UNRWA goes far beyond bureaucratic restructuring; it is an attempt to redefine millions of Palestinian refugees as so-called economic migrants, stripping them of their right to return, and recasting the challenge facing them as one of “absorption” in neighboring countries.

Another path to erasure has been the Oslo strategy, limiting the question of Palestine to promises of territorial sovereignty—promises that amount to fragmented self-rule across scattered enclaves in the West Bank and Gaza, with the exclusion of refugees and the vast majority of the Palestinian people. This playbook is drawn straight from the Bantustans of South African apartheid and the “Indian Reserves” of Canadian settler colonialism. It is a strategy ultimately aimed at cultivating a Palestinian political leadership that is willing to give a green light to other Arab states for the normalization project.

It is no coincidence that Saudi Arabia has openly signaled its readiness to normalize with Israel—so long as it comes with the symbolic concession of a “Palestinian state.” Even Algeria—long a vocal supporter of the Palestinian cause—has shifted in this direction, with its president announcing in early February 2025 his support for normalization in exchange for some kind of Palestinian statehood.

As with the Oslo years, all of this highlights the dangerous illusions embedded in the concept of “Palestinian sovereignty.” Such rhetorical gestures are fictional and performative; they have nothing to do with the fulfillment of Palestinian rights. Their goal is to erase Palestinian history, identity, and struggle—opening up the political legitimacy for Israel’s integration into the region. We should do well to remember the continuities between Oslo and the genocide in Gaza. Israeli strategy has always alternated between the periodic use of extreme violence and U.S.-sponsored negotiations—not as opposing forces, but as two sides of a single, continuous process of dispossession.

Freedom Is Global

The past 76 years have repeatedly shown that these efforts to permanently erase Palestinian steadfastness and resistance will fail. Despite the decades of fragmentation, a common identity and shared national experience continue to unite Palestinians—whether refugees, Palestinian citizens of Israel, or those in the West Bank, Gaza, and Jerusalem. Yet, while acknowledging the ongoing reality of dispossession, we must recognize that it has also been accompanied by the emergence of new social layers and class fractions in Palestinian society, alongside varying kinds of integration into Israeli capitalism. Understanding how these political and economic logics shape the Palestinian experience today is essential for any serious liberation strategy.

With this in mind, we argue for an alternative perspective to the dominant ways that Palestine is typically understood—whether a focus on supposedly interminable religious conflict, Israel’s massive human rights violations, or appeals to the neutrality of the international legal regime. These kinds of framings serve only to depoliticize and confuse. They make it difficult to build effective solidarity, because Palestine is treated simply as a moral imperative or an exception—something that stands apart from the bigger structures of global capitalism.

Palestine is treated simply as a moral imperative or an exception—something that stands apart from the bigger structures of global capitalism.

In contrast to these approaches, we instead emphasize the basic link between the dispossession of Palestinians and the politics of the wider Middle East region. Such an approach posits the struggle for Palestinian liberation not only as a confrontation with Israel, but also a challenge to the broader architecture of regional power. This is why Palestine has always been so fundamental to political movements across the Middle East. And, conversely, it is why the fate of Palestine is intimately bound up with the successes (and setbacks) of other struggles in the region.

These regional dynamics are a result of the Middle East’s pivotal role in our oil-centered, capitalist world. A fundamental aspect to the restructuring of capitalism after the Second World War was the rise of oil as the dominant fossil fuel, binding the expansion of American power to a new global energy order that we can describe as fossil capitalism. This shift repositioned the Middle East as a vital site of energy extraction while also making it a key battleground of anti-colonial struggle, where fights over sovereignty and resources were shaped by the imperatives of imperial control.

Today, the Gulf states, in close partnership with Western oil giants, are doubling down on hydrocarbon production, locking the planet into a trajectory of certain climate catastrophe. For the U.S., this deepening fossil fuel expansion—tied to its strategic alliance with the Gulf monarchies and their normalization with Israel—is a crucial source of power at a time when American global dominance faces mounting challenges. There can be no dismantling of the fossil order, nor any genuine Palestinian liberation, without breaking apart these alliances. This is why Palestine is at its core a struggle against fossil capitalism—and why the extraordinary battle for survival waged by Palestinians today, in Gaza and beyond, is inseparable from the fight for the future of the planet.

Editor’s note: This essay is adapted from Resisting Erasure: Capital, Imperialism and Race in Palestine by Adam Hanieh, Robert Knox, and Rafeef Ziadah, recently published by Verso.