Omar El Akkad: 'One Day There Will Be No More Looking Away.'

It is a disorienting thing, to keep a ledger of atrocity, to write the ugliness of each day as it happens.

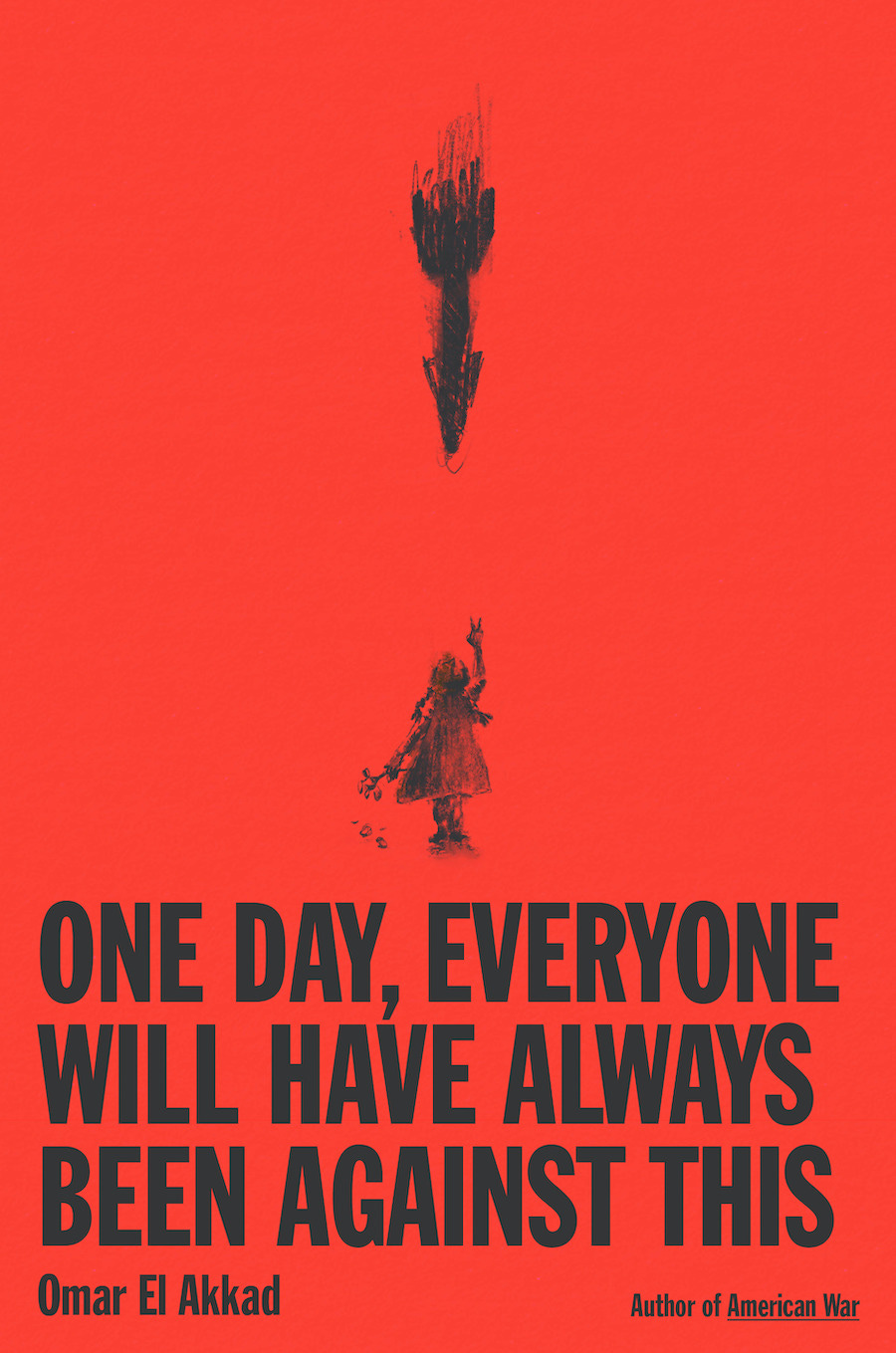

Editor’s note: In late October 2023, just a few weeks into Israel’s carpet bombing of Gaza in retaliation for the Hamas-led attacks of October 7, writer Omar El Akkad posted a tweet that has since been viewed more than 10 million times: “One day, when it’s safe, when there’s no personal downside to calling a thing what it is, when it’s too late to hold anyone accountable, everyone will have always been against this.”

That single sentence went on to form his searing book, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, which was published earlier this year and from which this essay is adapted. It is now a finalist for the 2025 National Book Awards for Nonfiction.

Born in Egypt, El Akkad grew up in Qatar, moved to Canada as a teenager, and now lives in Oregon. He is a former reporter for The Globe and Mail, where he covered the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, among many other beats. His acclaimed debut novel, American War, was published in 2017.

By Omar El Akkad

Omar El Akkad is an author and journalist. He is a two-time winner of both the Pacific Northwest Booksellers’ Award and the Oregon Book Award. His books have been translated into 13 languages.

It is a disorienting thing, to keep a ledger of atrocity, to write the ugliness of each day as it happens. The months smother the months, soon the years will smother the years. Killings that might have once made front-page news slowly submit to the law of diminishing returns—what is left to say but more dead, more dead? The stock market churns, the president steps aside, the future of the most powerful nation hangs by a thread. News is new, and whatever this is, it can no longer be called new. Maybe this is the truly weightless time, after the front page loses interest but before the history books arrive.

One day this will end. In liberation, in peace, or in eradication at a scale so overwhelming it resets history. It’ll end when sanctions pile up high enough, or the political cost of occupation and apartheid proves debilitating. When finally there is no other means of preserving self-interest but to act, the powerful will act. The same people who did the killing and financed the killing and justified the killing and turned away from the killing will congratulate themselves on doing the right thing. It is very important to do the right thing, eventually.

When the time comes to assign blame, most of those to blame will be long gone. There will always be feigned shock at how bad things really were, how we couldn’t have possibly known. There will be those who say it was all the work of a few bad actors, people who misled the rest of us well-meaning folks. Anything to avoid contending with the possibility that all this killing wasn’t the result of a system abused, but a system functioning exactly as intended.

For many people, that will be enough—a return to some more tolerable standard of subjugation. But for many, it won’t be, and the liberal class that acquiesced so begrudgingly to the least of measures will find that a sizable contingent who might have previously aligned with its ideals can no longer bring themselves to do so. Not after what has been done, what has been seen, what cannot be forgotten.

There will be more moments of terror, both state-sanctioned and coldly, brutally individual. Only some of these acts will be formally labeled terror, though, because in the hierarchy of the Western world—of the world entire—revenge is a carefully delineated thing, around which whole histories and peoples must be ordered to make certain violence regrettable but understandable and other violence savage and infinitely punishable. But none of this changes the reality that revenge has always been a universal resource. When the state enacts it, it will be deemed proportional and measured. When the individual does, it will mark a brand-new starting point of history and everyone who looks or sounds or in any way resembles the author of that violence will be commanded in perpetuity to condemn it, knowing full well no amount of condemnation will ever be enough.

One day there will be no more looking away. Looking away from climate disaster, from the last rabid takings of extractive capitalism, from the killing of the newly stateless. One day it will become impossible to accept the assurances of the same moderates who say with great conviction: Yes the air has turned sour and yes the storms have grown beyond categorization and yes the fires and the floods have made of life a wild careen from one disaster to the next and yes millions die from the heat alone and entire species are swept into extinction daily and the colonized are driven from their land and the refugees die in droves on the borders of the unsated side of the planet and yes supply chains are beginning to come apart and yes soon enough it’ll come to our doorstep, even our doorstep in this last coddled bastion of the very civilized world, when one day we turn on the tap and nothing comes out and we visit the grocery store and the shelves are empty and we must finally face the reality of it as billions before us have been made to face the reality of it but until then, until that very last moment, it’s important to understand that this really is the best way of doing things. One day it will be considered unacceptable, in the polite liberal circles of the West, not to acknowledge all the innocent people killed in that long-ago unpleasantness. The truth and reconciliation committees are coming. The land acknowledgments are coming. The very sorry descendants are coming. After all, grief in arrears is grief just the same. Entire departments of postcolonial studies will churn out papers interrogating the obliviousness that led us all to that very dark place, as though no one had seen from the beginning exactly what that place was, as though no one had screamed warnings at the top of their lungs back when there was time to do something. One day the social currency of liberalism will accept as legal tender the suffering of those they previously smothered in silence, turned away from in disgust as one does carrion on the roadside. Far enough gone, the systemic murder of a people will become safe enough to fit on a lawn sign. There’s always room on a liberal’s lawn.

The same people who did the killing and financed the killing and justified the killing and turned away from the killing will congratulate themselves on doing the right thing.

One day there will be an accounting, even as so often those who did the worst things imaginable in the killing fields were allowed to meld back into polite society. The man who put the bullet in the little girl’s head might return to coach Little League games. The patrol that opened fire on the starving civilians might meet up every now and then for karaoke nights, might celebrate what they did when it is still acceptable, but over the years grow quieter, and finally bond over a shared silence thicker than blood. The soldier who drove the tank over the handcuffed body, who heard the sound and felt the rupture, might come home to a high school sweetheart and get down on one knee and might have children of his own one day. People who proved themselves capable of the most monstrous things human beings can do to one another might be granted one final immunity, because what’s the alternative? To look into a neighbor’s eyes and see, barely visible, the kind of stain no amount of repentance will ever wash away? Who can live like that? Better to move on.

There will be people who never move on, who to the end of their lives struggle to unsee the image of the body turned to red paste, the child forced to eat animal feed, the bones pushing against the skin, the slow extinguishing of life at the hands of hunger, the older siblings who must tell the younger ones that everyone else is gone, the hastily dug graves vast against the horizon, like goose bumps on the flesh of the earth. And every time they hear a politician profess the supremacy of international law, of human rights, of equality for all, they will hear only the sounds of screaming.

And yet, against all this, one day things will change.

Alongside the ledger of atrocity, I keep another. The Palestinian doctor who would not abandon his patients, even as the bombs closed in. The Icelandic writer who raised money to get the displaced out of Gaza. The American doctors and nurses who risked their lives to go treat the wounded in the middle of a killing field. The puppet-maker who, injured and driven from his home, kept making dolls to entertain the children. The congresswoman who stood her ground in the face of censure, of constant vitriol, of her own colleagues’ indifference. The protesters, the ones who gave up their privilege, their jobs, who risked something, to speak out. The people who filmed and photographed and documented all this, even as it happened to them, even as they buried their dead.

It is not so hard to believe, even during the worst of things, that courage is the more potent contagion. That there are more invested in solidarity than annihilation. That just as it has always been possible to look away, it is always possible to stop looking away. None of this evil was ever necessary. Some carriages are gilded and others lacquered in blood, but the same engine pulls us all. We dismantle it now, build another thing entirely, or we hurtle toward the cliff, safe in the certainty that, when the time comes, we’ll learn to lay tracks on air.

Adapted from: One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This by Omar El Akkad. Copyright © 2025 by Omar El Akkad. Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC